"It was many and many a year ago

In a kingdom by the sea

That a maiden there lived whom you may know

By the name of Annabel Lee..."

The debate over which woman--or women--inspired what is arguably Poe's most beautiful poem has raged with remarkable vigor practically from the moment "Annabel Lee" first appeared in print, only days after the author's death.

It is a tribute to the unique emotional resonance of the poem that such a controversy even exists, considering that it is so overtly allegorical, rather than autobiographical, and there is certainly no valid evidence that Poe himself gave clues about any personal significance it may have had for him. (Poe was never one to offer explanations for any of his writings--in fact, he seemed to rather enjoy mystifying his readers with an air of, "It's none of my concern if you're too dull-witted to know what I mean.") However, this has not stopped Poe fans from linking his fable of the "kingdom by the sea" with virtually every woman he ever knew--something that, I suspect, would have both amused and disgusted him.

The leading actresses who have auditioned for the role of "Annabel Lee" are, roughly in order of popularity:

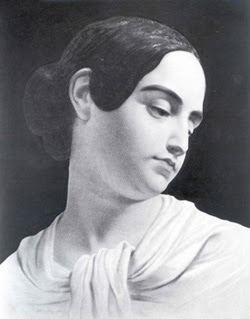

1. Virginia Eliza Clemm Poe

Poe's wife, is, by far, the woman most identified with the poem, and, while one Poe scholar perhaps became overly partisan when he said it was "sacrilege" to associate any other name with "Annabel Lee," she is the only logical choice if one wishes to read the lines as having any basis in fact.

The first to publicly state that the poem was a tribute to Virginia was Frances S. Osgood, in the "Reminiscences of Edgar A. Poe" she published in "Saroni's Musical Times" in December 1849. (Rufus W. Griswold later reprinted her account in his "Poe memoir.") Osgood's stated aim was to counter a current rumor that the poem was written in memory of a "late love affair" of the poet's. (It is not known if she was referring to Sarah Helen Whitman, Sarah Elmira Shelton, Sarah Anna Lewis, or some other lady--who hopefully was not named "Sarah.") Osgood commented disdainfully that "There seems a strange and almost profane disregard of the sacred purity and spiritual tenderness of this delicious ballad, in thus overlooking the allusion to the kindred angels and the heavenly Father of the lost and loved and unforgotten wife."

Whatever Osgood's motives may have been in making this assertion--whether it was out of spite against one of these other women, a desire to show intimate knowledge of the love between Poe and his wife, or simply a wish to give Virginia her due--she may have, for once, told the truth. Aside from the probability that Virginia was, as Mrs. Osgood conceded, his one genuine love, of all the women Poe knew, she was the only one who had "no other thought than to love and be loved by me," she alone was his "bride," and, of course, unlike the other leading candidates, she was dead when he wrote the poem. (The "wind" that "came out of the cloud, chilling/And killing my Annabel Lee" could be interpreted as a reference to Virginia's tuberculosis.) "Annabel Lee" is very possibly simply a lovely piece of imagery with no specific personal implications, but if Poe did intend it as autobiography, applying it to anyone other than his late wife is pure absurdity.

Not that this has stopped many people from trying.

2. Sarah Elmira Royster Shelton

Mrs. Shelton is the only other "Annabel" whose candidacy has developed any sort of following, in spite of the fact that her sole claim to the role rests upon a 1901 article by Edward Alfriend, "Unpublished Recollections of Edgar Allan Poe." Alfriend, who claimed to have been a friend of Shelton's (even though he gave her first name as "Elizabeth,") stated that she told him that Poe had assured her that she was his inspiration for the poem (and that she was the "lost Lenore," to boot!) Alfriend's piece is among the most easily-ridiculed Poe articles--it is packed from beginning to end with statements that are both easily disproved and manifestly ludicrous. It is impossible to read his "recollections" without coming to the conclusion that he didn't know the first thing about either Poe or Mrs. Shelton.

There is absolutely no other valid reason to link La Royster to "Annabel Lee," (and it should be noted that in the interview Mrs. Shelton allegedly gave Edward V. Valentine in 1875, she stated that Poe never addressed any poems to her.) Nevertheless, she still has her champions, most notably Thomas O. Mabbott.

Mabbott, as was often his habit in many other matters, gave varied and uncertain opinions about the poem's origins, but he was fondest of naming Mrs. Shelton as the poem's inspiration--largely, it seems, because of his strange antipathy towards Virginia Poe. For whatever reason, he swallowed whole all of Susan Archer Talley Weiss' unfounded slurs against Virginia and her marriage, making it impossible for him to accept the possibility that Poe had loved his wife enough to immortalize her memory in verse. (Mabbott was also under the impression that Poe wrote the poem during the brief period of his 1849 reacquaintance with Mrs. Shelton. He seemed oblivious to the fact that "Annabel Lee" was completed by the early spring of that year--months before Poe reconnected with his old neighbor.)

Here I must pause for an admittedly off-topic rant: What made all of Mabbott's pronouncements regarding Virginia all the more exasperating is the fact that--like other Poe biographers, most notably Hervey Allen, George Woodberry, and Frances Winwar--he seldom directly named Weiss as his source. He would instead write statements along the lines of, "Rosalie Poe's foster-brother John Mackenzie said..." or "Rosalie said..." or simply relate anecdotes without giving any source at all. (He often did this trickery with other sources as well.)

This was completely misleading Mabbott's readers. What he quoted was, rather, what Mrs. Weiss--a chronicler who made King Rufus himself seem a model of probity--alleged these people said to her. (Susan Weiss is also, lest we forget, the same person who asserted that Elmira Shelton instigated Poe's murder.) The fact is, we have no statements about Poe that come directly from any of the Mackenzies--I suspect they had only a formal social acquaintance with him--and nothing of any interest or importance from Rosalie, who made it clear to John H. Ingram that she had virtually no personal knowledge about her famous brother--she did not even know she had siblings until she was "a good size girl." In short, Mabbott, Allen, Winwar, Woodberry, et al, relied on uncorroborated and easily discredited hearsay. Mabbott's boast that, unlike others who wrote about Virginia, he was relying on the words of people who were close to Poe, while dismissing first-hand testimony from those who actually did know both the Poes, all of whom lauded Virginia and testified to the couple's devotion to each other, witnesses such as Maria Clemm, Lambert A. Wilmer, George Lippard, Mayne Reid, George R. Graham, Thomas C. Clarke and his daughter Anne, Mary Brennan, William Gowans--even Rufus W. Griswold and Frances S. Osgood, for crying out loud--makes one wonder if Mabbott wasn't permanently possessed by the Imp of the Perverse.

Mabbott's copious and incredibly influential writings (the question of how he obtained this influence is a mystery I will likely never solve) were usually not even bad scholarship--they were bad historical fiction.

3. Sarah Helen Power Whitman

What makes Mrs. Whitman stand out among the parade of Annabel wannabes is that she herself was the sole promoter for her connection to the poem. Sometime after Poe's death, she conceived the notion that "Annabel Lee" was written to her as a "peace offering." She insisted the poem disproved the common belief that Poe went to his grave harboring negative feelings towards her. (Although, in a letter to Rufus W. Griswold written two months after Poe's death, Mrs. Whitman evinced no personal knowledge about the origins of "Annabel Lee"--in fact, she even asked Griswold if he had any idea who had inspired the poem. He offered no opinion on the subject.) To the end of her life, Mrs. Whitman tried, with increasing desperation, to convince the world of her link to "Annabel Lee," and how it proved she had a special place in Poe's heart--despite the fact that she must have been aware that few people, if any, believed her. Of all the parade of possible Annabels, Mrs. Whitman's exercise in self-delusion is undoubtedly the saddest and most pitiful of the lot.

Next post: The Annabel Also-Rans.