"A lie will go round the world while truth is pulling its boots on."

-proverbial saying quoted by Charles Haddon Spurgeon

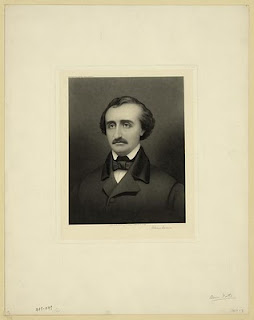

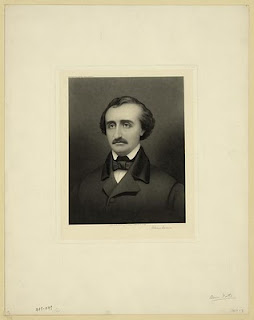

In December 1849, the magazine "Saroni's Musical Times" published Frances S. Osgood's version of her acquaintance with the late Edgar Allan Poe. The next year, Rufus Griswold incorporated her story in his "memoir" of Poe, although, with his usual blithe contempt for veracity, he presented her reminiscences as having been written at his request, for his benefit.

Griswold described Osgood's account of Poe as a defense of her dead friend, something to be placed beside his own "harsher judgments." Her recollections have been, without exception, seen as such ever since. As with everything else concerning Poe, I believe the truth is not that simple--or that benign. Read carefully and objectively, Osgood's surface veneer of cloying sentimentality masks a strong undercurrent of malice, even anger.

She began her tale by directly addressing the magazine's proprietor, Herman Saroni: "You ask me, my friend, to write for you my reminiscences of Edgar Poe. For you, who knew and understood my affectionate interest in him, and my frank acknowledgment of that interest to all who had a claim upon my confidence, for you, I will willingly do so."

This is interesting. Mrs. Osgood stated that only those who "had a claim upon my confidence" knew of her "affectionate interest" in Poe. Poe's modern biographers never tire of asserting that all of Poe and Osgood's contemporaries did little but share salacious gossip about their relationship. Yet here, the lady herself revealed the fact that no one outside her inner circle of intimates was aware she even had so much as an "interest" in him!

Rather knocks the whole "scandalous public flirtation" legend straight into the dustbin, does it not?

She continued by saying that her "affectionate interest" was one that was shared by every woman who had known Poe. In the next lines, however, she stated that when Poe had been drinking, "he was in the habit of speaking disrespectfully of the ladies of his acquaintance." Osgood said she found this hard to believe of the man who, she asserted, thought so highly of her that during the year of their acquaintance, he often sought her out for "counsel and kindness." (A footnote: I'd love to see some documentation proving this claim.) Then, she revealed she certainly did believe this charge by stating sharply that if he made such remarks, "the wise and well informed knew how to regard, as they would the impetuous anger of a spoiled infant, balked of its capricious will, the equally harmless and unmeaning phrenzy of that stray child of Poetry and Passion."

After this outburst--where she displayed her aptitude for "counsel and kindness" by dismissing the late poet as a "spoiled infant" whose "phrenzy" was to be ignored, she continued: "For the few unwomanly and slander-loving gossips who have injured

him and

themselves only by

repeating his ravings, when in such moods they have accepted his society, I have only to vouchsafe my wonder and my pity. They cannot surely harm the true and pure, who, reverencing his genius and pitying his misfortunes and his errors, endeavored, by their timely kindness and sympathy, to soothe his sad career."

The condescending and heavily italicized indignation Osgood demonstrated towards Poe's "ravings" and the "unwomanly" (she obviously had some particular woman or women in mind) "gossips" showed a real sense of personal affront. Obviously, the "ladies" Poe had somehow disparaged--"ladies," Osgood seethed defensively, who had only sought to offer him "kindness and sympathy" (so reminiscent of her earlier claim to have given him "kindness and counsel")--included herself.

In the sweet-and-sour manner that characterized her entire account, Osgood then gave a vague and saccharine glimpse of Poe in the sanctuary of his home ("wayward as a petted child,") and related an occasion when, answering an "affectionate summons" from Virginia Poe, she "hastened" to their lodgings. Upon arrival, she found Poe just completing his series on "The Literati of New York."

"'See,' said he, displaying in laughing triumph, several little rolls of narrow paper, (he always wrote thus for the press,) 'I am going to show you, by the difference of length in them, the different degrees of estimation in which I hold all you literary people.'"

Then, according to Osgood, he and Virginia playfully unrolled all his papers, until they laughingly opened one that stretched clear across the room.

"'And whose lengthened sweetness long drawn out is that?' said I. 'Hear her!' he cried, 'just as if her little vain heart didn't tell her it's herself!'"

Mrs. Osgood certainly presented a memorable image of Poe's domestic life--husband and wife both falling all over each other to trumpet their slavish adoration of the incomparable Frances Sargent Osgood. This nauseating little anecdote is a perfect example of her prose fiction at its most mawkish, but it is impossible to reconcile the idea of Poe behaving in this cutesy fashion with anything approaching reality. All one can say about Mrs. Osgood's efforts to place the Poes on her own infantile level is to cite Poe's own manuscript notes for his uncompleted book, "The Living Writers of America." He commented that the defect of the "Literati" series was "that the length of each article was naturally taken as the measure of the author's importance--this arose from [the] fragmentary character of the papers, which were rifacimentos."

After Osgood took care to establish Poe and Virginia's hero worship for her, she described her introduction to the poet at the Astor House, sometime in March 1845. In an unwittingly revealing line, she wrote that he greeted her "calmly, gravely, almost coldly." She claimed that, a few days before, Nathaniel P. Willis gave her a copy of "The Raven," saying the author wanted her opinion of it, and desired to meet her.

There are several obvious improbabilities in this anecdote. First, at the time in question, "The Raven" had already been published and was the talk of New York. There is no possible way Osgood was unfamiliar with the poem. Second, although Poe had briefly worked for Willis on the "New York Mirror," he had by then left the paper. Willis himself later recorded that he and Poe never socialized, and that apart from occasional accidental meetings on the street, he only knew Poe from their mutual time in the "Mirror" offices. (And, of course, he never corroborated any of Osgood's story.) In fact, Willis stated in December of 1846 that he had had no contact at all with Poe for two years--i.e., since Poe left the "Mirror." Third, it would have been totally uncharacteristic for Poe to have done something so demeaning as begging introductions to married magazine poetesses whom he had no reason to meet. He certainly had never done so before. It is far more likely that Osgood herself sought an introduction. Finally, we have a letter Osgood herself wrote to Sarah Helen Whitman shortly after she first met Poe. She boasted--rather tactlessly, considering Whitman was a rival poet--that she had been told Poe praised Osgood's work in a recent lecture, and that she had recently met him, and liked him very much. She says nothing of how they met, or anything indicating he had sought an introduction, or desired her opinion of his most popular poem. Surely, if she had had any such details which further illustrated Poe's regard for herself, Osgood would have included them.

Osgood's recollections go on to state that she spent much of 1845 traveling for her health (it is true that, as far as her activities can be traced, she spent little time in New York during that year.) She claimed that, while out of town, she and Poe corresponded, thanks to the "earnest entreaties" of Virginia, who, she said, lauded the "restraining and beneficial effect" Osgood's "influence" had on him. She noted that she herself never saw Poe intoxicated, but intimated that was

only because he had promised

her to refrain from drinking. According to our Fanny, his wife's desire to keep him sober counted for little by comparison.

Any comment on the astonishing childlike egotism of Osgood's account would be superfluous. But even if this pitiful tale was true--and simple common sense revolts at the idea--what does it say about Osgood's true regard for Poe and his wife? She would have it that Edgar was a drunken weakling whom only she could control, and Virginia was someone who had so feeble a hold on her spouse, and so little pride, that she had to beg another woman to use her "influence" (by mail?!) to keep him on the straight-and-narrow.

In that same sweetly catty vein, Osgood described the "charming love and confidence that existed between his wife and himself" "in spite of the many little poetical episodes, in which the impassioned romance of his temperament impelled him to indulge."

Even her assertion that "Annabel Lee" was a tribute to Virginia, "the only woman whom he ever truly loved," possibly had a barbed edge. Osgood may have been sincere (she certainly owed Virginia at least that much.) However, her denial of the report that the poem dealt with "a late love affair" of Poe's aroused the ire of Sarah Helen Whitman. Immediately after Poe's death, Whitman had launched a campaign to convince the world that "Annabel Lee" was written for her, and she interpreted Osgood's statement as a deliberate insult to herself. After writing to Osgood's friend Mary Hewitt about the matter (Osgood herself was dead by then,) Whitman told others that Hewitt assured her that Osgood was not disputing

her claims to the poem. Hewitt believed Osgood simply lied about Virginia being the poem's inspiration in order to attack another Poe groupie, "Stella" Lewis, who was asserting

she was the real Annabel. (Just to add the final unpleasantly self-serving touch to her story, Whitman also claimed that Hewitt wrote that she was sure Osgood did not believe a word of her statement that Virginia had been Poe's one true love.) Whitman did not preserve Hewitt's letters, (deliberately?) so we cannot know if this is what Hewitt actually wrote. As neither Hewitt nor Osgood would have had any personal knowledge about Poe's inspiration for his loveliest poem, it really does not matter. It is interesting, though, that even in what appeared to be a sincere tribute to Poe and Virginia's love, Osgood may have been motivated not by honesty and friendship, but by cheap spite towards other women.

Osgood concluded her little history in the same disagreeable vein in which she began, by approvingly quoting an insulting Poe elegy written by her friend Richard Henry Stoddard:

"He might have soared in the morning light

But he built his nest with the birds of night!

But he lies in dust, and the stone is rolled

Over the sepulchre dim and cold;

He has cancelled all he has done or said,

And gone to the dear and holy dead,

Let us forget the path he trod,

And leave him now, to his Maker, God."

About the only other thing one can say about Osgood's remarkable account is that it is proof that, contrary to what is commonly assumed, there was no suggestive gossip about her relations with Poe during his lifetime. We certainly know about unpleasant talk that circulated concerning Poe and women in 1846, but it all centered on the dispute involving Elizabeth Ellet and

her dealings with Poe--not Osgood. Even aside from her unwittingly revealing admission to Saroni mentioned at the beginning of this post, if Osgood's relationship with Poe had brought her into disrepute, she--not to mention Griswold--would hardly have been so eager to inform the world that she was the one Poe went to for "kindness and counsel." Or that only

her influence, not Virginia's, had weight with him. Or that they carried on a "divinely beautiful" correspondence (which, of course, no longer exists--if it ever did--aside from

a brief note to her from Poe that addresses Osgood as "Dear Madam" and reads like a form letter.) Or that she would need to assure her audience that, although she and Poe never met after the first year of their acquaintance, they remained friends until his death. If there had been any nasty rumors circulating about the pair, both she and her champion Griswold would be anxious to bury all these details, not wave them like a flag. Her account reads not like a woman attempting to downplay their relationship, but one desperate to establish that a relationship existed.

Unfortunately, her way of doing so was to portray Poe as a man who drunkenly slandered innocent women who merely offered him "kindness and sympathy." She described him as someone whom only she could keep on the path of righteousness. She depicted him as having "little poetical episodes" with other women (such as herself?) under the nose of his adoring wife. Not a pretty picture, and I cannot but believe that was precisely her intention. Shakespeare wrote, "the whirligig of time brings on its revenges," and Frances Osgood was having hers on the dead Poe and Virginia for having rejected her. After the Ellet fiasco, the Poes left New York without telling anyone--including Osgood--where they had gone. Despite Osgood's various efforts over the following years to initiate contact with him, Poe never spoke or wrote to her again. For someone as self-absorbed and egotistical as she was, this slight must have been intolerable. (Incidentally one of the many, many curious features about her "reminiscences" is that they appeared

anonymously in "Saroni's." The world had no idea she was this chatty "friend" of Poe's until Griswold recycled her story--after her death. One wonders if Mrs. Osgood didn't feel a twinge of bad conscience about publishing such an obviously fictional account.)

And to think, this farrago of lies, self-deification, and petty malisons is presented as a

tribute to Poe. It is small wonder that her close friend Griswold was so eager to republish it in his Poe biography.

(Images: NYPL Digital Gallery, Library of Congress Prints & Photographs Division.)

There is a tradition that Edgar Allan Poe's sister Rosalie was born on December 20, 1810, but there is no solid documentary evidence for this claim. All we know is that she was born long enough after the mysterious disappearance of her mother Eliza's husband, David Poe, for questions to arise about the child's paternity. It has even been claimed that David's sister, Maria Poe Clemm, maintained that Rosalie was not the true child of either David or Eliza Poe. Intriguingly, when Rosalie was a child, a wealthy resident of Richmond, Virginia, Joseph Gallego, died and left a will bequeathing the then enormous sum of 2,000 dollars for Rosalie's maintenance. She was the only charity bequest in his will to be so favored, leaving one to speculate whether the young orphan was more to him than just an object of sympathy.

There is a tradition that Edgar Allan Poe's sister Rosalie was born on December 20, 1810, but there is no solid documentary evidence for this claim. All we know is that she was born long enough after the mysterious disappearance of her mother Eliza's husband, David Poe, for questions to arise about the child's paternity. It has even been claimed that David's sister, Maria Poe Clemm, maintained that Rosalie was not the true child of either David or Eliza Poe. Intriguingly, when Rosalie was a child, a wealthy resident of Richmond, Virginia, Joseph Gallego, died and left a will bequeathing the then enormous sum of 2,000 dollars for Rosalie's maintenance. She was the only charity bequest in his will to be so favored, leaving one to speculate whether the young orphan was more to him than just an object of sympathy.