"A sad thing it was, no doubt, very sad; but we can't mend it. Therefore let us make the best of a bad matter; and, as it is impossible to hammer anything out of it for moral purposes, let us treat it æsthetically, and see if it will turn to account in that way. "On December 30, 1899, the "New York Evening Post" published a strange, almost impressionistic article entitled "The Bones of Annabel Lee." The author, who gave his name only as "J.P.M.," claimed that in 1846, while working as a messenger boy in New York City, he made several visits to Fordham to deliver manuscript proofs to Edgar Allan Poe.

-Thomas De Quincey, "On Murder, Considered As One of the Fine Arts"

His most vivid memories of these visits were the brief glimpses he caught of the dying Virginia Poe. "The recollection of her appearance is still vivid as of a picture of a saint seen long ago in a receding light," he wrote. "Her large dark eyes...affected me with something like a searching omnipresence..." "Poor Annabel Lee was doomed. They saw her slipping away softly and wonderingly, as if the mystery and inevitableness of it all had grown to be an abiding and pensive question." "J.P.M." also described an occasion when, while in the Fordham cottage, he and Poe overheard Virginia, who was in the next room, coughing. He remembered how her husband winced at the sound.

The doomed young woman left such a haunting impression on "J.P.M.," that thereafter he, with "personal zest," sought out from his acquaintances in the literary world anything they knew personally about Poe and his wife. He said that those who had known the poet believed that "the tenderest part of his nature was to be found in the idealization of his child-wife. It is quite possible that that idealization was...not at all practical, or to her best material comfort. But there she was, an absolute antithesis to the actual world, which did not understand him and chafed and aggravated him beyond endurance..." Poe "would obtain special relief in obedience" to his fragile wife.

The doomed young woman left such a haunting impression on "J.P.M.," that thereafter he, with "personal zest," sought out from his acquaintances in the literary world anything they knew personally about Poe and his wife. He said that those who had known the poet believed that "the tenderest part of his nature was to be found in the idealization of his child-wife. It is quite possible that that idealization was...not at all practical, or to her best material comfort. But there she was, an absolute antithesis to the actual world, which did not understand him and chafed and aggravated him beyond endurance..." Poe "would obtain special relief in obedience" to his fragile wife.He closed by repeating William Gill's macabre anecdote (of which Gill seemed unaccountably proud) about retrieving Virginia's "few, thin, discolored bones" from her Fordham grave and keeping them in his bedroom. "J.P.M.," unaware of Gill's claims that he eventually brought his ghoulish bric-a-brac to Baltimore for reburial, added eerily, "I presume that the fragments of poor Annabel Lee are wandering about..."

Mid-way through his narrative, "J.P.M." abruptly switches from his dreamlike musings on Virginia Poe to a story involving her husband and another dead woman--Mary Rogers.

As fans of both Poe and true-crime literature know, Rogers worked as a shopgirl for a New York tobacconist, John Anderson. Her unsolved 1841 murder was later immortalized by Poe in his story "The Mystery of Marie Roget." Poe always intimated he had "inside information" about the murder, even that he knew the identity of the killer--or, the man responsible for what he told George Eveleth was "the accidental death arising from an attempt at abortion"--supposedly a naval officer from a family prominent enough to protect him. This has never been proven, and could well be just another example of Poe's fondness for--as we today would put it--messing with people's minds. On the other hand, the particular interest he took in what would seem to be a relatively unimportant "cold case" could be interpreted as a sign that he was aware of some hidden depths to Rogers' murder which are now lost to us. Poe's contemporaries found his attempts to play detective so notable that forty years after his death, when John Anderson's will was being contested, it was suggested during the court proceedings that the tobacconist had paid Poe to write "Marie Roget" in order to clear Anderson from any suspicion that he had a hand in the crime!

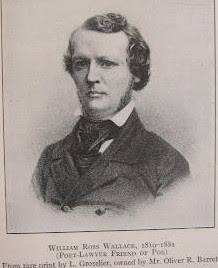

That is, of course, a strange charge. But "J.P.M." related a story that, if it is at all to be trusted, is even stranger. He claimed to have heard this account directly from someone called only "the late tobacconist," but who was obviously Anderson. According to "J.P.M.," Poe called on Anderson sometime in 1846. The exact reason for his visit was not stated, but it had something to do with "Roget," which had been republished the previous year. Anderson then invited Poe to dinner at "the old Holt Hotel." The meal did not go well. According to Anderson, Poe and the poet William Ross Wallace, who was also dining with them, got into a violent quarrel over the Rogers case. Anderson claimed the incident left him with the impression of Poe as a young hothead who had allowed the dinner champagne to derange him.

That is, of course, a strange charge. But "J.P.M." related a story that, if it is at all to be trusted, is even stranger. He claimed to have heard this account directly from someone called only "the late tobacconist," but who was obviously Anderson. According to "J.P.M.," Poe called on Anderson sometime in 1846. The exact reason for his visit was not stated, but it had something to do with "Roget," which had been republished the previous year. Anderson then invited Poe to dinner at "the old Holt Hotel." The meal did not go well. According to Anderson, Poe and the poet William Ross Wallace, who was also dining with them, got into a violent quarrel over the Rogers case. Anderson claimed the incident left him with the impression of Poe as a young hothead who had allowed the dinner champagne to derange him.

"J.P.M." said he afterwards asked Wallace about the incident. Wallace essentially confirmed Anderson's account, but indicated that the tobacconist had misconstrued Poe's behavior. Poe was neither drunk nor violent, according to Wallace, but his nerves were badly strained as a result of his dying wife's desperate condition. When, at dinner, he perceived that Anderson was attempting to gain publicity for his business by capitalizing on his former shopgirl's death, Poe's disgust with him only blackened his mood further.

So, what really happened? Did Poe seek Anderson out after the publication of "Marie Roget?" If so, why? Did this dinner at the Holt Hotel truly take place? If it did, again, what was the purpose? And what cause could Poe and Wallace have to fight over the Rogers murder?

"Bones of Annabel Lee" could well be just another example of the journalistic fiction so common in the public press of the era. If there is any truth to it, however, it hints that the Mary Rogers murder may have been a far bigger story than even Poe dared to fully say.

No comments:

New comments are not allowed.